|

|

| Click Here to Return to Home Page |

This web page serves as an introduction to Armenian Rugs and highlights the contribution made by Armenians to the art form of rug weaving, primarily in the Caucasus region.

|

Historical Perspective

Armenians are the earliest known weavers of oriental rugs. Ulrich Schurmann, a reknowned expert on oriental rugs, believes that the Pazyryk rug, the world's oldest known rug (5th cent. B.C.), can be attributed to the late Urartians, or early Armenians, based on the rug's structure, design, and motifs [1].

Marco Polo and Herodotus are among the many observers and historians who recognized the beauty of Armenian rugs. They noted the rugs' vivid red color which was derived from a dye made from an insect called "ordan" (Arabic "kirmiz"), found in the Mount Ararat valley. The Armenian city of Artashat was famous for its "ordan" dye and was referred to as "the city of the color red" by the Arab historian Yaqut [1].

It is also theorized that the word "carpet", which Europeans used to refer to oriental rugs, is derived from the Armenian word "kapert", meaning woven cloth. The Crusaders, many of whom passed through Armenia, most likely brought this term back to the West. Also, according to Arabic historical sources, the Middle Eastern word for rug, "khali" or "gali", is an abbreviation of "Kalikala", the Arabic name of the Armenian city Karnoy Kaghak. This city, strategically located on the route to the Black Sea port of Trabizond between Persia and Europe, was famous for its Armenian rugs which were prized by the Arabs.

"The Armenians and Greeks who lived intermingled among the Turcomans ... weave the choicest and most beautiful carpets in the world " Marco Polo

Geographically located at the crossroads of many great empires, including the Persian, Ottoman, and Russian, Armenians lived scattered throughout the Caucasus and the Anatolian Plateau, as well as other parts of the Middle East, Europe, and the Far East. Although under foreign rule for most of their history, Armenians were the leading artists, architects, and merchants within these empires.

The merchants in Armenia, in particular, used this dispersed network of expatriated Armenians to their advantage as they acted as the middle-men for trade between the Mediterranean, Asia, and Europe. By the 14th century this trade network was firmly established between Northern and Southern Europe. Thus, many Armenian rugs made their way to Europe. This is evidenced by the appearance of Armenian rugs in many European paintings, the most notable of them being Hans Holbein's (1425-1524) portrait of George Gyze, a merchant who is depicted as sitting at a table covered with a popular Armenian Kuba rug [2].

The Role of The Armenian Carpet in Society

The invention of the Armenian alphabet in 406 A.D. marked the beginning of the golden age in Armenian literature. The writings, paintings, and illuminated manuscripts produced in this era provide insight to the significance of the role of the carpet in Armenian society and oriental rugs in general. The written histories and heroic tales contain references to the Armenian rug. Armenian miniature paintings of royalty and religious scenes as well as the famous illuminated manuscripts also contain many illustrations of Armenian rugs.

Armenian rugs were status symbols that were placed on the floor or hung on the wall to create an ambiance within the home, palace, or church. Dining on rugs was customary among Armenians and non-Armenians. The numerous kings, emperors, caliphs, sultans, and princes that presided over the Armenians prized these beautiful Armenian rugs and often demanded them as part of a yearly "tax" along with mules, falcons, and salt-fish[1]. Extravagant rugs, woven with gold or silver threads, were placed on the thrones and at the feet of Armenian royalty.

The Armenian Church, which adopted Christianity in 301 A.D., regarded the Armenian rugs as treasures of the church. Although prayer rugs are today associated with Islam, historical references confirm that Armenian prayer rugs were woven by Armenians well before the emergence of Islam in the 7th century. Rugs were also woven to commemorate a special event, such as a royal wedding, or to honor the dead. Rugs were placed on coffins during royal funeral processions and would be buried along with the coffin.

The Caucasian Armenian Rug

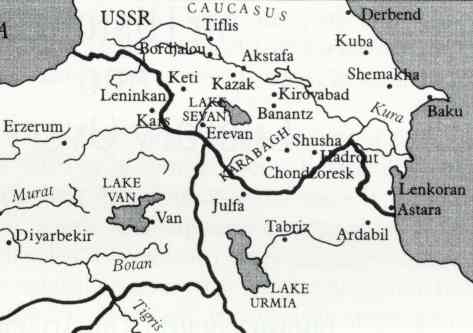

Geographically, the Caucasus are located between the Black and Caspian seas, the gateway between Europe and Asia. Inhabitants of the Caucasus are primarily Armenians and Azerbaijani (Azeri) Turks with a smaller number of Georgians and Kurds. Other ethnic groups include the Abkhaz, Circassians, Chechens, Lesghians, Mingrelians, Svans, Laz, and Talish. Although there is a wealth of historical information available about the Caucasus, the rugs from this region are commonly misrepresented. Many Caucasian rugs are often labeled "Cabistan" or "Kazak". However, these names do not correspond to any known geographical location or groups of people. Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact origins of the "Kazak", it can be traced to the area in the south Caucasus, between Tiflis and Erevan. According to official Russian census figures for the late 19th century, it is most likely that Armenians and Azeris who were living side-by-side in this region wove the "Kazak" rugs. Caucasian rugs can not be classified based on patterns as is common with Persian and Turkish rugs. Because rugs were commonly traded throughout the region, rug patterns were widely dispersed and would inevitably be copied. In order to identify and classify Caucasian rugs their construction must be examined. This includes the variance in the color of the warp, the arrangements of the strands, the dyed color of the weft, the way the ends are finished, the way the sides are bound, and the quality of the wool (i.e. coarseness vs. lustrous). A typical Armenian rug contains a division of fields, medallions, and motifs that employ geometric shapes. A large proportion of the inscribed Armenian rugs contain cross shapes, human figures, and geometric bird and animal figures not commonly found in non-Armenian rugs. These animal figures and crosses are believed to have religious significance since they are consistent with motifs found in Armenian manuscripts and relief sculptures on Armenian churches and monasteries [1]. Also, the use of red cochineal dye, which has been documented as being produced by Armenians, is common among the inscribed Karabagh rugs [1]. H. M. Raphealian has studied the meanings of symbols in oriental rugs, including Armenian rugs, for over 50 years. Interestingly, he believes that many of the motifs used in Armenian rugs and Armenian art in general, were a result of Armenia's contact with Asia, particularly India and China, as early as the 4th century A.D. [2]. Some of these motifs include figs, Asoka trees, pine cones, turtles, serpents, and birds. Provincial village women were the primary weavers of rugs, although there are Armenian inscriptions referring to male weavers. All of the rugs were woven with wool, which was locally obtainable. Cotton was only used as weft threads and for edging. According to Arthur T. Gregorian, "Armenian rugs are woven firmly with the nap clipped very low, making the rugs supple and soft. A great preference is shown for delicate shades of soft blue, touches of green, coral, old gold, and tans. All the patterns are outlined in either natural brown or wool dyed to this shade"[3]. The weavers knew that over time this brown color would fade faster than the other colors, thus it was used for outlining motifs. This color was obtained from the use of an iron pyrite in dyeing the wool.

Common Armenian Rugs

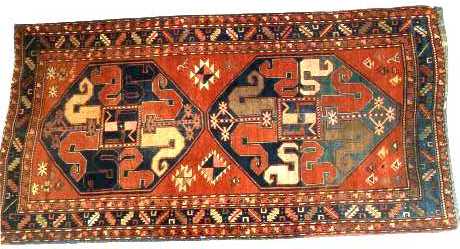

Kazak Rugs As stated above, the term "Kazak" does not correspond to any known tribe of people. The Kazak rugs were woven in the area between Tiflis and Erevan, a region mainly inhabited by Armenians even today [4]. In general, the Kazak rugs contain large scaled patterns, several medallions, and bright contrasting colors.

There are three types of Kazak rugs [4]: 1. Bordjalou - a district south of Tiflis whose rugs are coarsely woven, contain simpler designs such as many latch hooks, and use vibrant colors including madder red, blue, ivory, and natural brown. 2. Rugs from the area south of Bordjalou and north of Erevan - These rugs have a shorter pile, are larger, have fewer wefts between each row of knots, and contain more formal medallion designs. 3. Rugs from Erevan and areas to its southeast including Echmiadzin, Ekhegnadzor, Martuni, and Shamshadeen - These rugs are thinner, double wefted, up to 15 feet long, and contain simpler designs. The more common colors are red and darker shades of blue, with less ivory. Karabagh Rugs Karabagh refers to a region, not an ethnic group. The population of Karabagh is mainly comprised of Armenians and Azeris. However, the population in the larger cities of Mountainous Karabagh, including Shushi, Stepanakert, and Agdam were, and still are, mostly Armenian. The Karabagh village rugs are similar to the Kazaks. They are all wool, have a thick pile, a coarse weave, and are double wefted. The most notable design is known as the Eagle Kazak, or the Sunburst rug. There are several Sunburst rugs containing Armenian inscriptions in existence [1]. Murray Eiland considers these rugs the ancestors of the famous 16th century Dragon rugs, which contain elongated geometric animal and plant forms, because they are most similar in texture, design, details, color and structure [1]. Due to the complexity of the Dragon rugs it is believed that they were woven near an industrial city, most likely Shusa, where fine materials and a variety of color dyes were available [4].

Another Karabagh village rug is referred to as the Cloudband Kazak because its medallions contain multiple "S" shaped forms which resemble Chinese Cloudbands. These carpets are variable in construction and were woven over a wide geographical area. However, there are also several Cloudband Kazak's containing Armenian inscriptions.

Genje Rugs Genje, also known as Kirovabad or Elizabethpol, is an area also inhabited by Armenians and Azeris. The rugs of Genje are also very similar to the Kazaks and Karabaghs in their knotting, pile, and texture. Some of the distinguishing characteristics include the multiple colors used in binding the sides, an uncolored wool warp, and red or light gray wool weft strands. The designs of the Genje rugs contain smaller repeating geometric patterns, often in a diagonal arrangement (see rug below). They are typically more blue and white and are lighter in color.

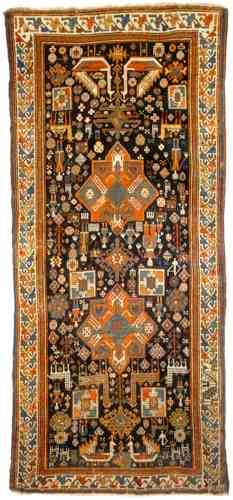

Shirvan Rugs Shirvan is south of the Greater Caucasus and east of Genje. Rugs from this region containing Armenian inscriptions have been collected, although the population is mostly Azeri, with small groups of Armenians and Tartars. These rugs have a shorter pile than the other rugs listed, finer knotting, a white woolen weft, and a warp consisting of brown strands twisted with white. There are many designs, including some with Persian influence, meaning that they are more floral than geometric. The main colors employed are blue and ivory and the rugs are not as bold as Kazaks. Many of the rugs are prayer rugs.

Akstafa rugs, a sub-type of Shirvan rugs, are runners containing medallions and stylized birds (Note birds at the top and bottom of the rug below). As mentioned above, the use of animals is common in Armenian rugs. In addition to conventional Shirvan rugs a few Akstafa rugs containing Armenian inscriptions have been cataloged [1].

Definitions (taken from [1]): Warp - The warp threads run vertically through the length of a textile. The threads making up the warp are stretched on the loom before weaving begins. When the rug is completed and cut from the loom, the exposed ends of the warps make up the fringe. Warp material may be wool (which is most common in Armenian rugs), cotton, silk, or, rarely, bast fibers. Weft - The weft threads are inserted perpendicularly to the warps, and the run across the loom. They may be made of any of the same materials as the warps, but they are ordinarily visible only from the back of the rug. The number of wefts that pass from side to side between the rows of knots are referred to as shoots. Armenian rugs may from the Caucasus and Anatolia have 2 or more shoots between the rows of knots, but in parts of Persia, Armenian rugs may have only a single shoot. At times the wefts are dyed. Pile - The manner in which the yarn is twisted around the warps to form pile is described as the "knotting" process, and we refer to each segment of pile as a "knot". There are 2 common types of knots, the Turkish (or symmetrical) and the Persian (or asymmetrical). All but a few Armenian rugs are symmetrically knotted. The "knot count", or number of tufts of pile in a given unit of area, is one measure of a rug's quality. Edge finish - Often the manner in which the edges are overcast (covered with a simple running stitch or selvaged (finished with a woven band) gives us information relative to the rug's origin. The purpose of both overcast and selvage is to reinforce the edges, which are particularly susceptible to wear. Sources:

|

|

| Click Here to Return to Home Page |